[Reversing] Reversing Faronics - Deep Freeze to locate DOS and Heap Overflows

Hi to all! We are again back here. In this post we will cover how to reverse engineering Faronics - Deep Freeze (legacy) software to locate different vulnerabilities, and how to trigger this vulnerabilities to get a (till the moment) DoS in the DFServerService.

Exploiting those vulnerabilities is out of the scope of this post, and i hope we can speak about that in the subsequent publications but spoiler this is a Heap Overflow, and my knowledge is not so deep yet to exploit that kind of vulnerabilites.

The application

The application we will use is Faronics Enterprise Server in version 8.38.220 which is an old one, and the majority of bugs existing in this application have been patched in the new one, although still it’s possible to trigger a DoS because of reading unallocated memory, as we will see next.

This application has a client - server architecture, and is useful in case you need to preserve the state of a host without being modified, as for example in a school.

Let’s do it

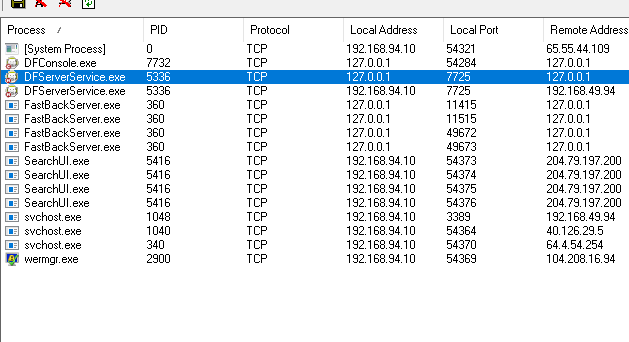

Initially we will see which services runs that application and very fast the one called DFServerService.exe running in port 7725 draws our attention.

If we try to open the EXE with IDA Pro we will see it is packed with UPX, but we can fastly unpack it with CFF Explorer.

Next, we will open WinDBG, IDA Pro and the native client of the application, so we can see how a legit client works and what kind of data it sends.

When opening it with Ida Pro we can see quickly that it is importing recv function from wsock32 DLL, so let’s use Cross-Reference utilities of Ida Pro to see where it is being called.

While reviewing recv caller functions we see the first strange thing. When pushing arguments in the stack, it doesn’t use ebp+offset to reference variables and doesn’t use even an structure approach, as could be the following,

mov ebx, [ebp-offset]

add ebx, 0x10

push ebx ; pushes for example buf

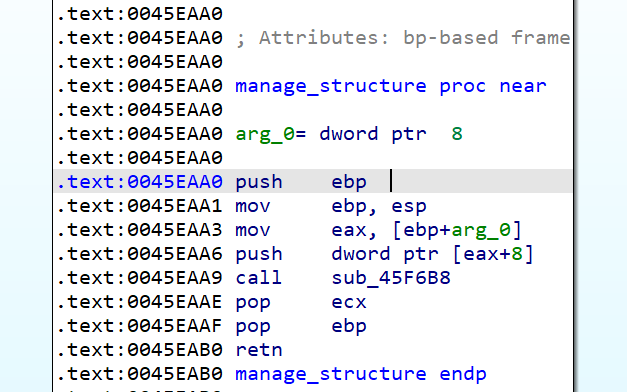

Instead it uses always the eax register, and pushes it to another function that will move eax+8 to yet another function that also will get eax+8 and latter, with that, it will reference a relative offset from that modified eax register.

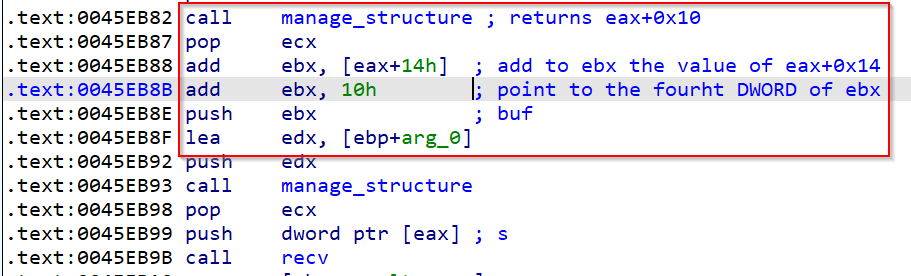

This has been named managestructure in Ida Pro

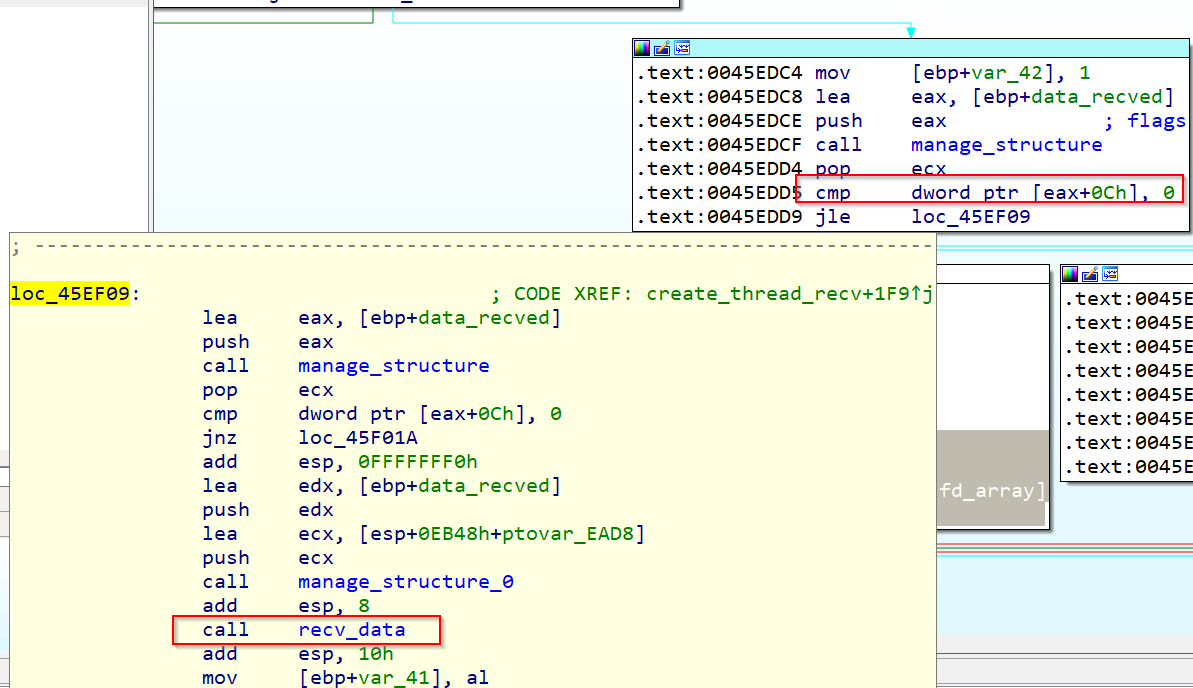

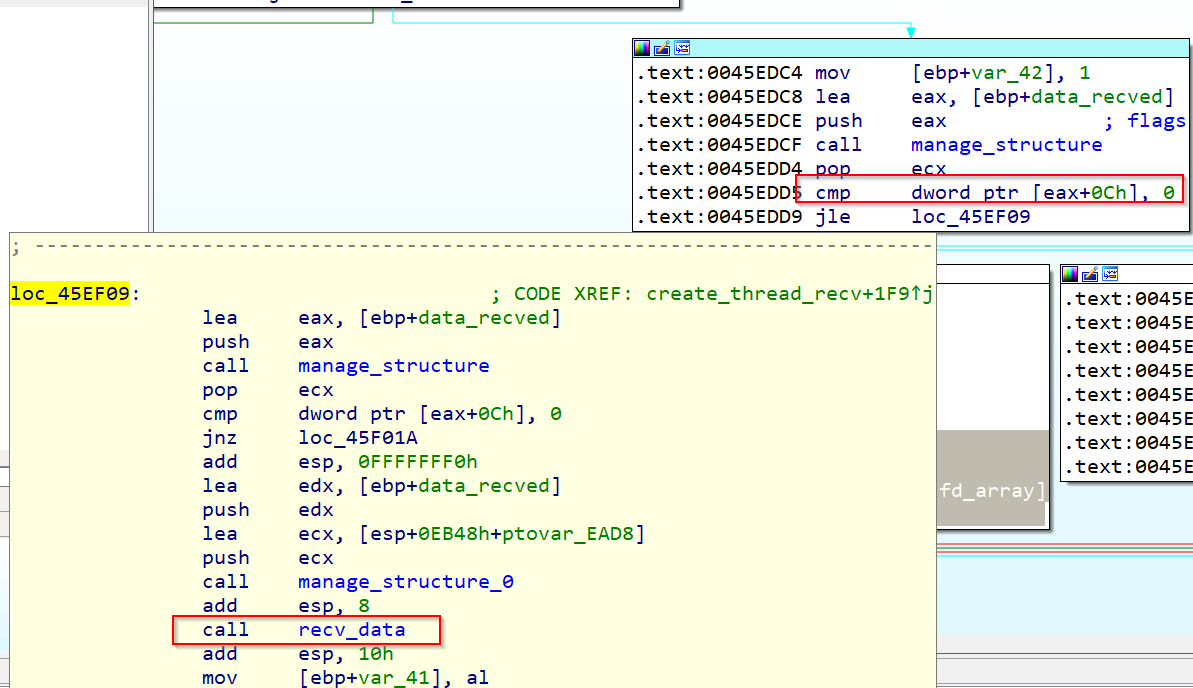

With all this in mind let’s deep dive the flow of the application, and check where will be the received buffer used again, to try to find possible vulnerable paths.

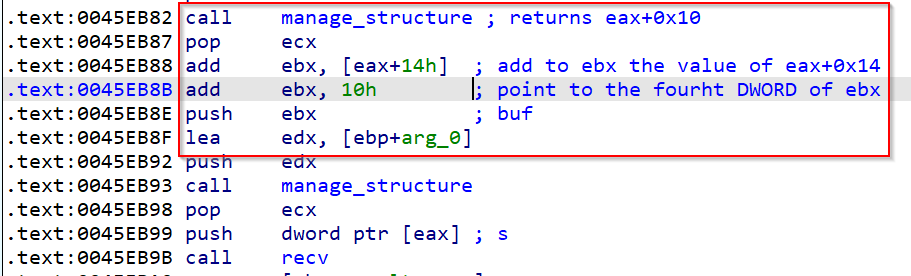

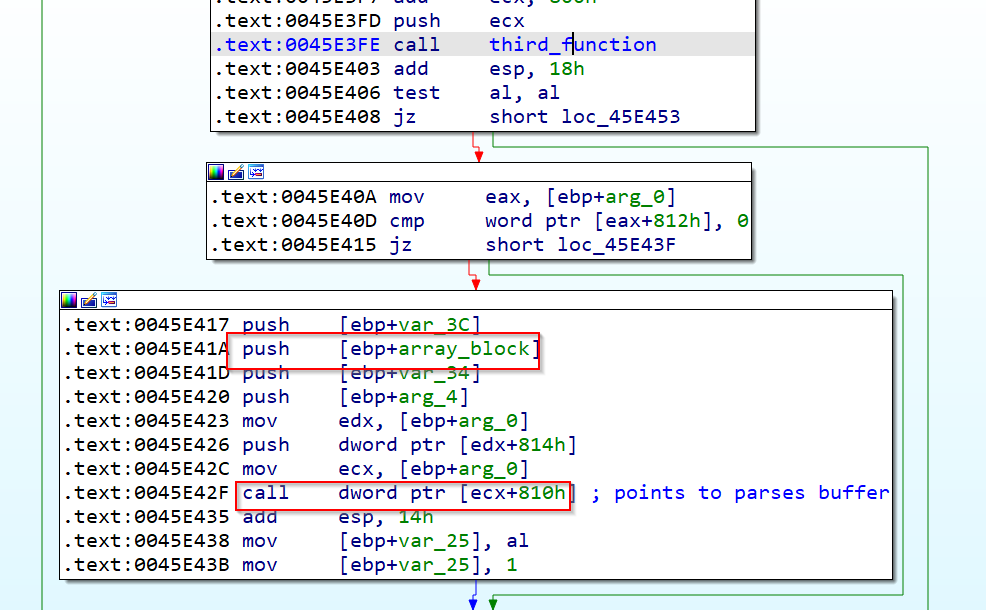

Reviewing how buf parameter is passed to the recv function, we observe that initially the address of [ebp+8] is being passed to the eax register, later this register is pushed in the stack as an argument for the function manage_structure, this will return the address of the buffer pointed by eax+0x10, later, the value pointed by eax+14 is added to ebx, that points to eax+0x10, and finally, the last add ebx, 0x10 will point to the 4rd DWORD of the structure pointed by ebx, finally this value is pushed as the buffer where data will be received.

Following that structure in the Ida flow graph seems very difficult, because it depends on a variety of other values, so in this case we will use a hardware breakpoint on the address of the buffer, to see in which other places this structure is being used.

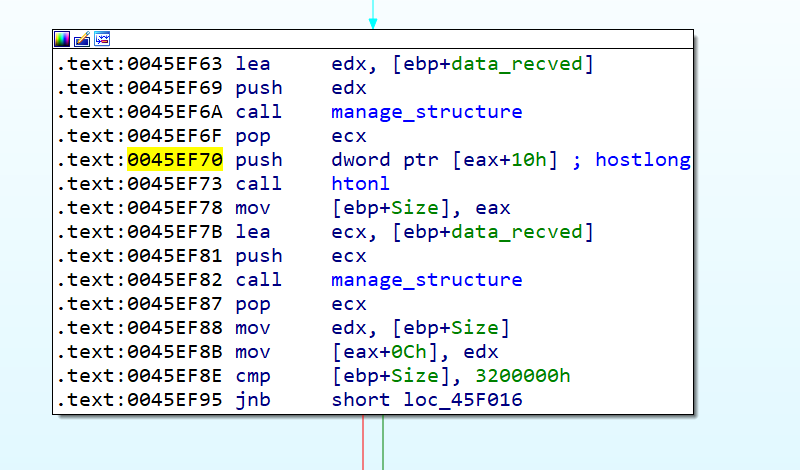

We let the program run after setting the hardware breakpoint, and we see how the execution flow is stoped after a push dword ptr ds:[eax+10] instruction

The buffer is passed to a htonl function and later the return will be compared with the value 0x3200000 depending if the value returned by htonl is below or not, the flow will follow one path or another.

Watching the possibilities it’s difficult to identify which one is better, because both could end in a call to a Sleep function, that will latter jump again to the begginning of the function, and after checking an unknown value, a new recv function could be triggered.

After trying and trying harder to send the appropiate data to pass this check without getting results, i thought about using the native client of the application, that obviosly will know how to communicate with the server, and see what it is sending to the first recv function to trigger the second one, so let’s do it.

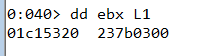

Using the client, we can identify that it sends a big DWORD value to the first buffer.

Latter we set a bp in the second recv function to check if we are reaching it with this initial value, and see what kind of data we are receiving there.

As we can see, this time we are receving data, this doesn’t seem ASCII data, we will see why latter, also we see that in the first recv the client is sending the value 0xa37b0300, so let’s continue with the execution of the the client to see where the second buffer is being used again.

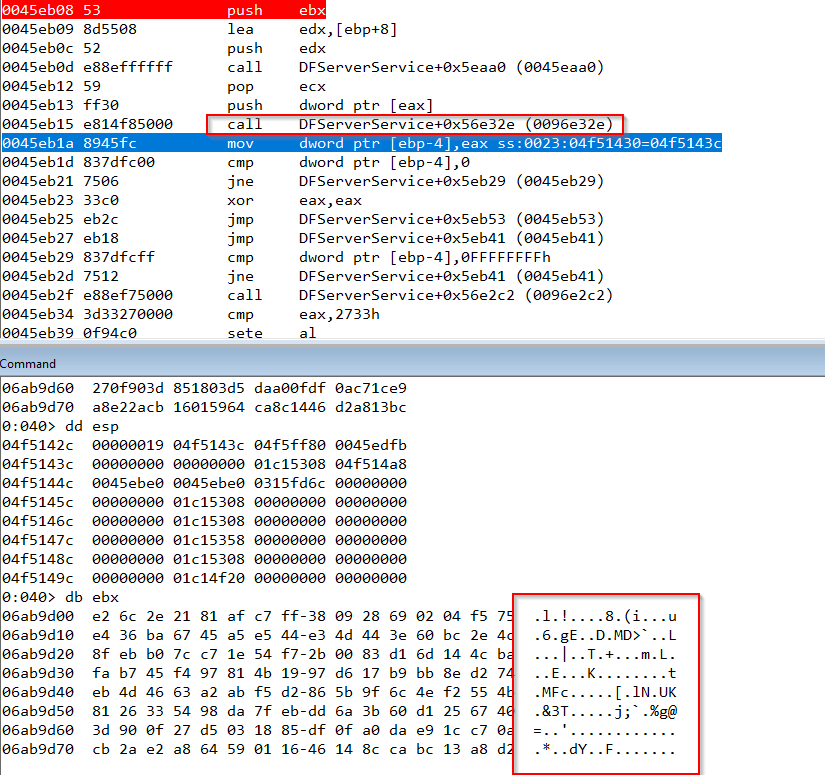

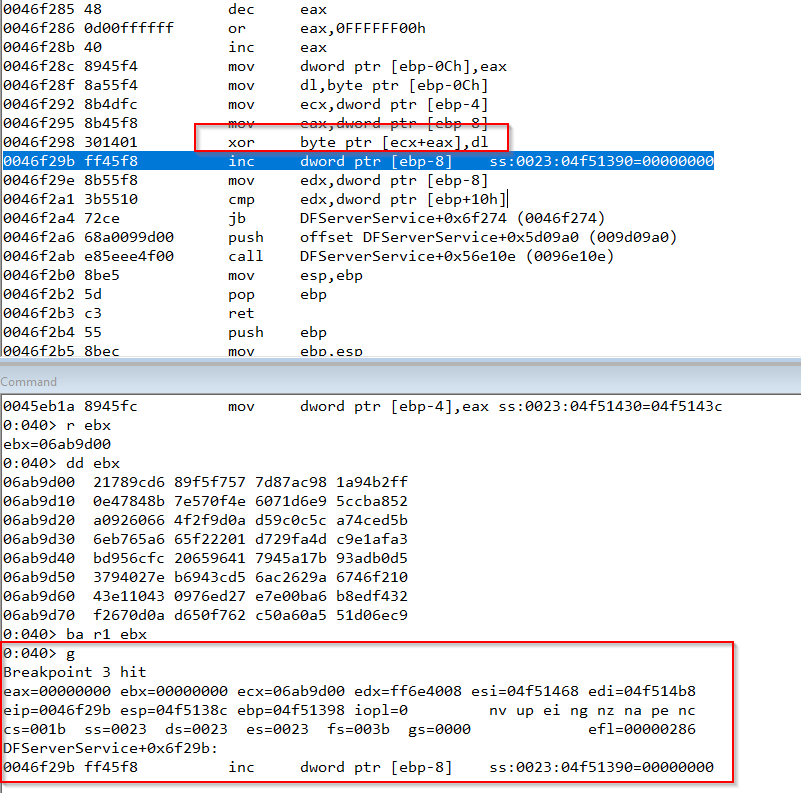

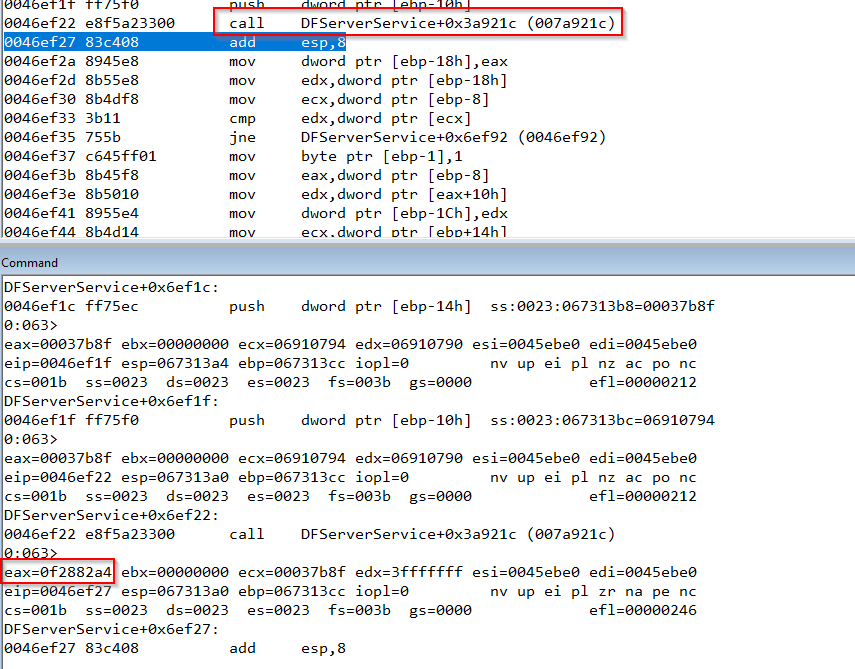

We use again a hardware breakpoint in the recv buffer, we continue the execution, watching the debugger is stopped in the following instruction.

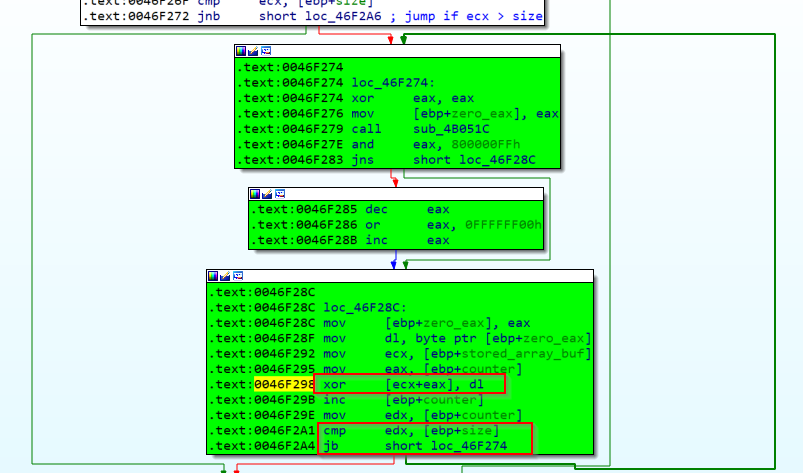

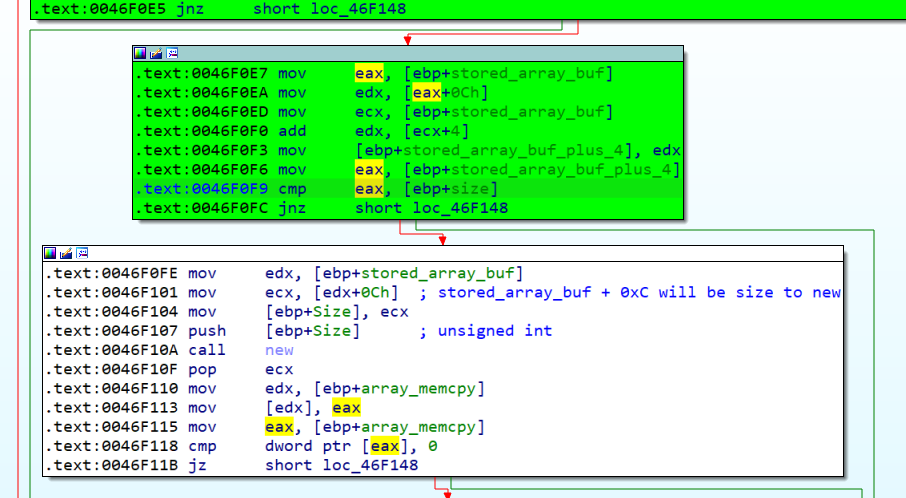

Watching this function in IDA we can observe that the buffer is being cyphered with a xor operation, inside a for loop, so we need to know why this is happening and what the cyphering keys are.

Prior to analyze the xor function, we need to know if it’s necessary to discover the xor keys, or if we can go on in the program execution without knowing this, so let’s look over the function to see if the buffer xored is being used again, and if this usage is interesting to us.

.text:0046F28C

.text:0046F28C loc_46F28C:

.text:0046F28C mov [ebp+zero_eax], eax

.text:0046F28F mov dl, byte ptr [ebp+zero_eax]

.text:0046F292 mov ecx, [ebp+stored_array_buf] //ecx comes from stored_array_buf

.text:0046F295 mov eax, [ebp+counter]

.text:0046F298 xor [ecx+eax], dl //ecx being xored

.text:0046F29B inc [ebp+counter]

.text:0046F29E mov edx, [ebp+counter]

.text:0046F2A1 cmp edx, [ebp+size]

.text:0046F2A4 jb short loc_46F274

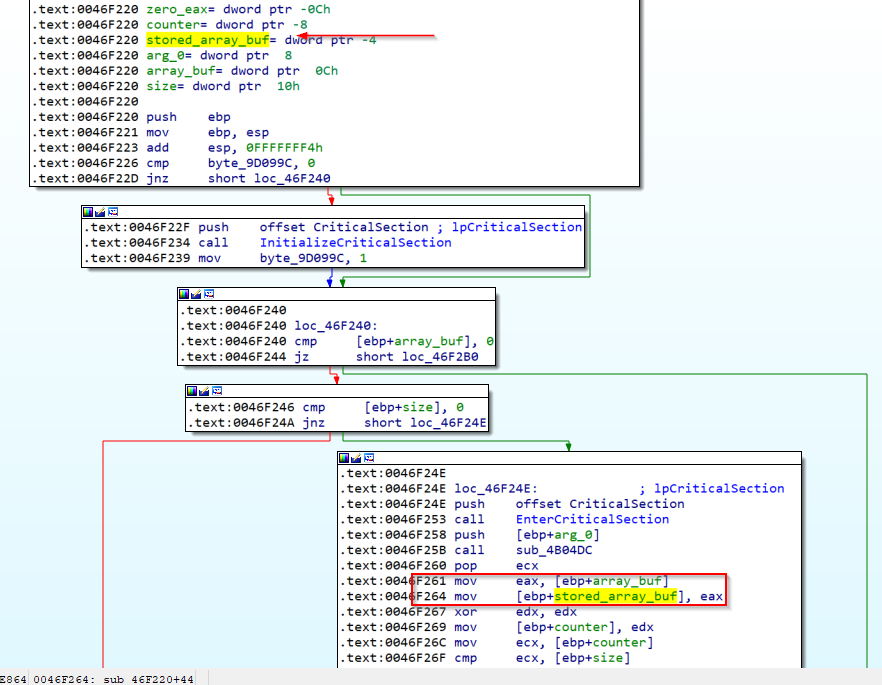

We see that ecx comes from an array that we renamed as stored_array_buf, so let’s see where it comes from.

It didn’t take us long to discover that stored_array_buf comes from one of the arguments that the caller passed to the called (current) function.

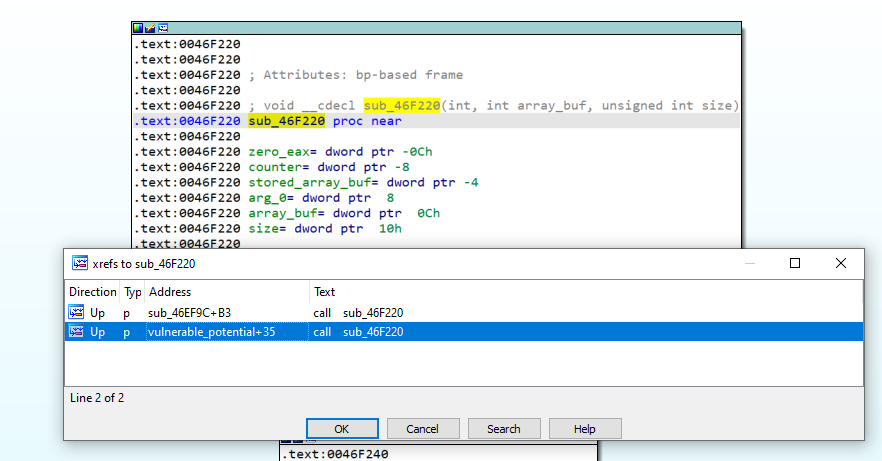

Let’s now see which the caller of this function is, and if the buffer is being used again after being xored.

We have two functios that reference the xorer function, we will use the second one.

.text:0046F09A loc_46F09A:

.text:0046F09A mov edx, [ebp+array_buf]

.text:0046F09D mov [ebp+stored_array_buf], edx ; keeps pointer to (not yet) xored buffer in stored_array_buf

.text:0046F0A0 push [ebp+size]

.text:0046F0A3 push [ebp+array_buf] ; buffer xored

.text:0046F0A6 push [ebp+arg_4]

.text:0046F0A9 call xorer_function

.text:0046F0AE add esp, 0Ch

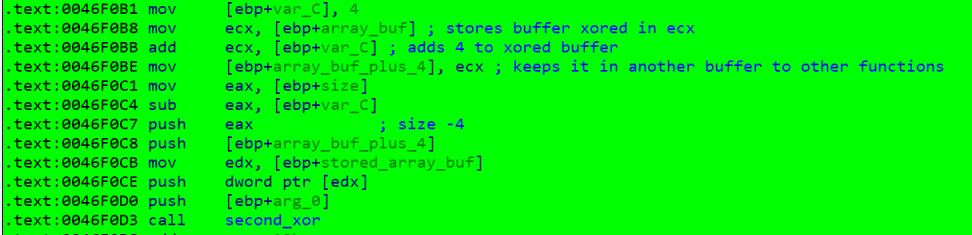

.text:0046F0B1 mov [ebp+var_C], 4

.text:0046F0B8 mov ecx, [ebp+array_buf] ; stores buffer xored in ecx

.text:0046F0BB add ecx, [ebp+var_C] ; adds 4 to xored buffer

.text:0046F0BE mov [ebp+array_buf_plus_4], ecx ; keeps it in another buffer to other functions

.text:0046F0C1 mov eax, [ebp+size]

.text:0046F0C4 sub eax, [ebp+var_C]

.text:0046F0C7 push eax ; size -4

.text:0046F0C8 push [ebp+array_buf_plus_4]

.text:0046F0CB mov edx, [ebp+stored_array_buf]

.text:0046F0CE push dword ptr [edx]

.text:0046F0D0 push [ebp+arg_0]

.text:0046F0D3 call sub_46F1B4

.text:0046F0D8 add esp, 10h

.text:0046F0DB mov ecx, [ebp+stored_array_buf] ; mov xored_buffer to ecx

.text:0046F0DE cmp dword ptr [ecx+8], 0A953h ; compares xored_buffer+8 with 0x0A953

.text:0046F0E5 jnz short loc_46F148

As wee can see the output of the xored_array_buffer is being compared with 0x0A953, and as we will see now, depending if we pass this check or not, we can find the first DoS vulnerability.

In the previous image can be seen how if we pass the check against 0x0A953 we can send an arbitrary value to the new function, including negative values, that would crash the application, to do that, we would need to send a packet with the following structure.

+-------------------------+

| First recv |

+------------------------ +

| 0xa37b0300 |

+-------------------------+

| Second recv |

+-------------------------+

| AAAA |

| offset to first memcpy |

| 0x0A953 |

| Size to new - offset |

+-------------------------+

As we can see, if we force the packet to send a negative size and compense it with the offset, we will pass the cmp eax, [ebp+size]; jnz check, and we will be able to force the new function to have a negative value.

So, only with that we would have a DoS vulnerability, but first we need to reverse engineer the xor encryption algorithm.

Reversing the xor

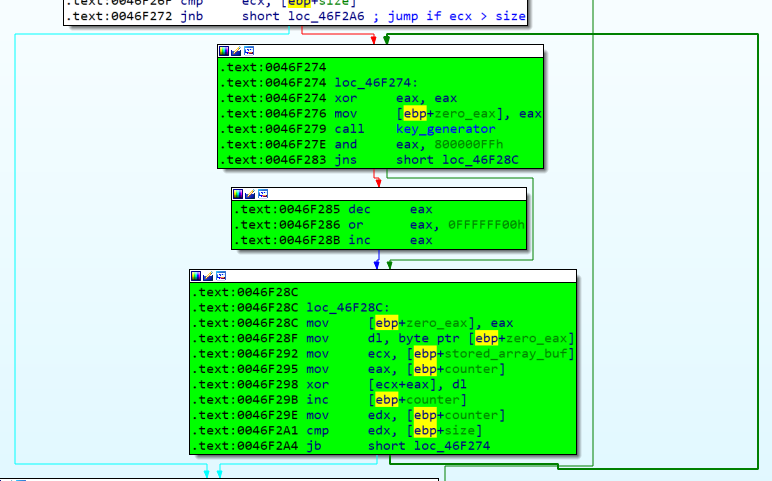

Focusing on the xor algorith, we must initially say that the data we send is xored twice, each time with a different key, so we will need to reverse two key generators.

The first one can be found in 0x0046F220 and looks like this

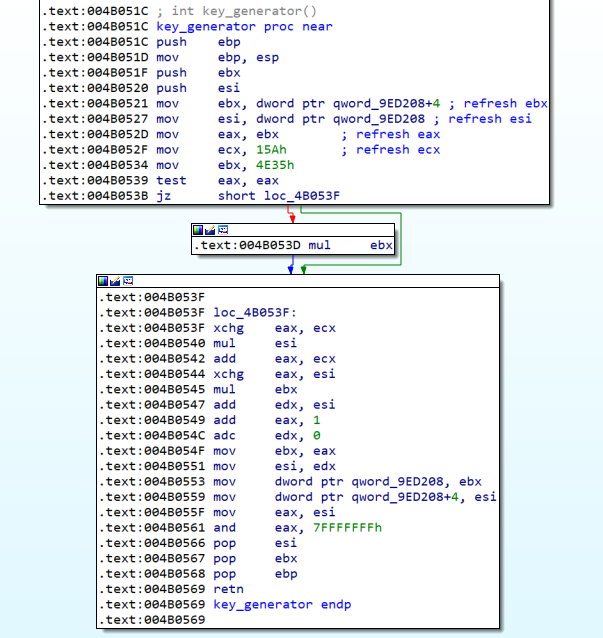

The key_generator function has the following code.

The code explained is below.

.text:004B0521 mov ebx, dword ptr qword_9ED208+4 ; saves in ebx a static value

.text:004B0527 mov esi, dword ptr qword_9ED208 ; saves in esi static value

.text:004B052D mov eax, ebx ; moves to eax ebx

.text:004B052F mov ecx, 15Ah ; moves to ecx 0x15A

.text:004B0534 mov ebx, 4E35h ; moves to ebx 0x4E35

.text:004B0539 test eax, eax ; check if eax == 0 (The first iteration will be)

.text:004B053B jz short loc_4B053F ; jump if eax == 0

.text:004B053D mul ebx ; multiplies eax * ebx and stores result in EDX:EAX

.text:004B053F

.text:004B053F loc_4B053F: ; exchanges data between eax and ecx

.text:004B053F xchg eax, ecx

.text:004B0540 mul esi ; multiplies eax * esi and stores data in EDX:EAX

.text:004B0542 add eax, ecx ; add ecx to eax --> eax = eax+ecx (ecx points to the old eax)

.text:004B0544 xchg eax, esi ; exchanges eax with esi

.text:004B0545 mul ebx ; multiplies eax (old esi) with ebx and stores in EDX:EAX

.text:004B0547 add edx, esi ; add ebx with esi ebx = ebx+esi

.text:004B0549 add eax, 1 ; add 1 to eax

.text:004B054C adc edx, 0 ; if the last add permutes the first bit of eax, we increase edx by 1

.text:004B054F mov ebx, eax ; moves eax to ebx

.text:004B0551 mov esi, edx ; moves edx to esi

.text:004B0553 mov dword ptr qword_9ED208, ebx ; reset the second static value with the current value of ebx

.text:004B0559 mov dword ptr qword_9ED208+4, esi ; reset the first static value with the current value of esi

.text:004B055F mov eax, esi ; mov esi to eax

.text:004B0561 and eax, 7FFFFFFFh ; eax = eax & 0x7fffffff

.text:004B0566 pop esi

.text:004B0567 pop ebx

.text:004B0568 pop ebp

.text:004B0569 retn ; return eax

And the python code that performs this key generation is below:

value = 0x00000000

value2 = 0x68527209

def generate_key():

global value #set value as global

global value2 #set value2 as global

ebx = value #ebx = static value

esi = value2 #esi = static value 2

eax = ebx #eax = ebx

ecx = 0x15A #ecx = 0x15A

ebx = 0x4e35 #ebx = 0x4e35

if (eax!=0): #test eax, eax; jz

eax = eax*ebx #multiplies and stores result in EDX:EAX

edx = (eax & 0xffffffff00000000) >> 0x20

eax = (eax & 0xffffffff)

temp_eax = eax # xchg eax, ecx

temp_ecx = ecx

eax = temp_ecx

ecx = temp_eax

eax = eax * esi #mul esi and stores in EDX:EAX

edx = (eax & 0xffffffff00000000) >> 0x20

eax = eax & 0xFFFFFFFF

ecx_value = ctypes.c_uint32(ecx).value #force ecx to be only a DWORD (python doesn´t have a DWORD type)

ecx = ecx_value

eax += ecx #add ecx to eax

eax = ctypes.c_uint32(eax).value #forces eax to DWORD

temp_esi = esi #xchange esi, eax

temp_eax = eax

esi = temp_eax

eax = temp_esi

eax = eax*ebx #mul ebx

edx = (eax & 0xffffffff00000000) >> 0x20

eax = eax & 0xffffffff

edx = edx + esi #add edx, esi

edx = ctypes.c_uint32(edx).value

carry_flag = bin(eax)[2] #python (sucks) implementation of adc edx, 0

eax += 1

if (carry_flag != bin(eax)[2]):

edx+=1

ebx = eax #end function

esi = edx

value2 = ebx

value = esi

eax = esi

eax = eax & 0x7fffffff

if (len(hex(value))>10 or len(hex(value2))>10):

print("No funciono: "+ hex(value) + " y " + hex(value2))

eax = eax & 0x800000FF #after the function returns another and operation is done

if (eax > 0x7fffffff): #check if value is signed or not

eax = eax-1

eax = eax | 0xffffff00

eax += 1

print("Negative")

return eax

It’s important to point that after the function is returned, the value is again bitwise anded with the value 0x8000000FF, that is the reason why exists this and in the python code.

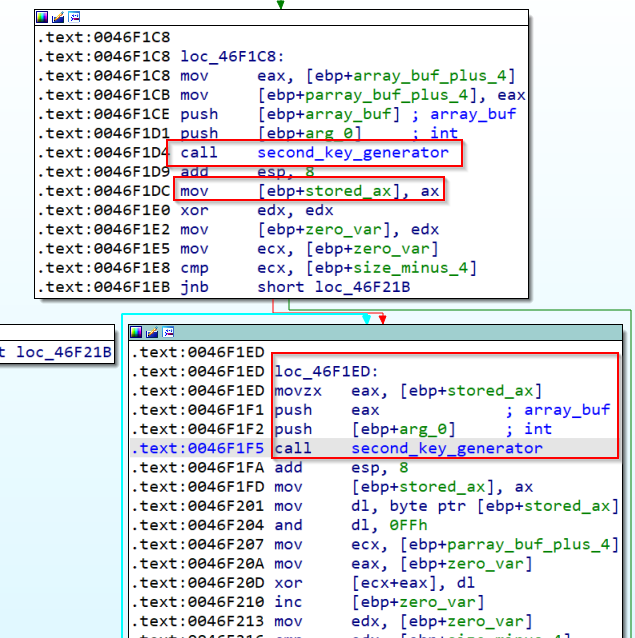

With this we could generate the first key, but as we said before, exists two xor operations, and the second is done with another key.

Let’s now analyze the second xor.

To get started we may see what the arguments of the function are.

This function takes as arguments the input_buffer address plus 4.

Looking inside the function, we see two checks prior to the key generator, but those are very easy ones.

After passing those checks we see a first call to a key_generator, this will receive as arguments the buffer and an unkown buffer, and once inside we see the following code.

.text:0046F150 push ebp

.text:0046F151 mov ebp, esp

.text:0046F153 push ecx

.text:0046F154 push ebx

.text:0046F155 mov eax, [ebp+array_buf]

.text:0046F158 mov ecx, 0B1h ; '±'

.text:0046F15D xor edx, edx

.text:0046F15F div ecx

.text:0046F161 imul ecx, edx, 0ABh ; '«'

.text:0046F167 mov eax, [ebp+array_buf]

.text:0046F16A mov ebx, 0B1h ; '±'

.text:0046F16F xor edx, edx

.text:0046F171 div ebx

.text:0046F173 add eax, eax

.text:0046F175 sub ecx, eax

.text:0046F177 mov [ebp+var_4], ecx

.text:0046F17A mov ax, word ptr [ebp+var_4]

.text:0046F17E and ax, 7FFFh

.text:0046F182 pop ebx

.text:0046F183 pop ecx

.text:0046F184 pop ebp

.text:0046F185 retn

.text:0046F185 second_key_generator endp

This code will do the following arithmetic operations.

1. mov to eax the pointer to the buffer

2. mov to ecx the value 0x0B1

3. edx = 0

4. eax = eax // ecx && edx = eax % ecx

5. ecx = edx * 0x0AB

6. move to eax the pointer to the buffer

7. move to ebx the value 0x0B1

8. edx = 0

9. eax = eax // ebx && edx = eax % ebx

10. eax = eax + eax

11. ecx = ecx - eax

12. move ecx to var4

13. move to the 16 bits register of EAX (ax) the value of var4 (ecx)

14. eax = ax & 0x00007FFF

15. return eax

This function will be called in a first step to initialize the value of EAX, and later it will be called in a foor loop to generate a dynamic xor key.

Once the key is generated, the buffer (except the first four bytes) will be again xored, and this buffer will be latter compared to 0x0A953 as we saw before.

The python code to implement this algorithm is shown below.

initiator = 0x41414141

def generate_key_2():

#init with AAAA

global initiator

eax = initiator

ecx = 0x0B1

edx = 0x0

edx = eax % ecx

eax = eax // ecx

ecx = edx * 0x0AB

eax = initiator

ebx = 0x0B1

edx = 0x0

edx = eax % ebx

eax = eax // ebx

eax += eax

ecx = ecx - eax

if (ecx < 0):

ecx = ecx & (2**32-1)

ax = ecx & 0xffff

ax = ax & 0x7fff

initiator = ax

ax = ax & 0x0ff

return ax

generate_key_2()

iterator = 0

second_key = []

while (iterator < (0x100-4)):

second_key.append(generate_key_2())

iterator+=1

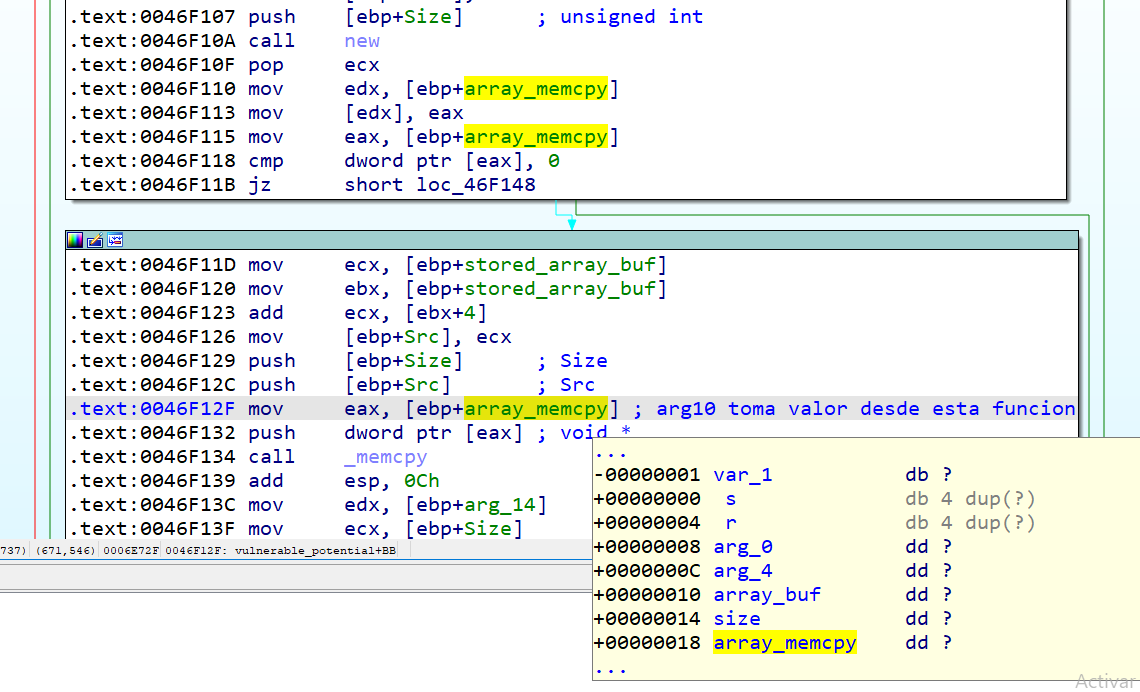

Now we could choose to exploite the previously alluded DoS vulnerability, but if we want to go on looking for other vulnerabilities, me must consider that the memcpy will copy the unxored buffer into ebp+18.

Now we can see that this ebp+18 is the fifth argument that the caller is passing to the function.

.text:0046F074 Src= dword ptr -1Ch

.text:0046F074 Size= dword ptr -18h

.text:0046F074 stored_array_buf_plus_4= dword ptr -14h

.text:0046F074 array_buf_plus_4= dword ptr -10h

.text:0046F074 var_C= dword ptr -0Ch

.text:0046F074 stored_array_buf= dword ptr -8

.text:0046F074 var_1= byte ptr -1

.text:0046F074 arg_0= dword ptr 8

.text:0046F074 arg_4= dword ptr 0Ch

.text:0046F074 array_buf= dword ptr 10h

.text:0046F074 size= dword ptr 14h

.text:0046F074 array_memcpy= dword ptr 18h

.text:0046F074 arg_14= dword ptr 1Ch

Viewing how the caller function pushes arguments to the called function, we see that this argument has been passed by lea edx, [ebp+array]; push edx

.text:0045E3A2 mov [ebp+size_readed], eax

.text:0045E3A5 lea edx, [ebp+size_readed]

.text:0045E3A8 push edx ; unsigned int *

.text:0045E3A9 lea ecx, [ebp+array]

.text:0045E3AC push ecx ; array_memcpy

.text:0045E3AD push [ebp+size] ; size

.text:0045E3B0 push [ebp+array_buf] ; array_buf

.text:0045E3B3 mov eax, [ebp+arg_0]

.text:0045E3B6 push dword ptr [eax+8] ; int

.text:0045E3B9 mov edx, [ebp+arg_0]

.text:0045E3BC add edx, 7F8h

.text:0045E3C2 push edx ; int

.text:0045E3C3 call vulnerable_potential

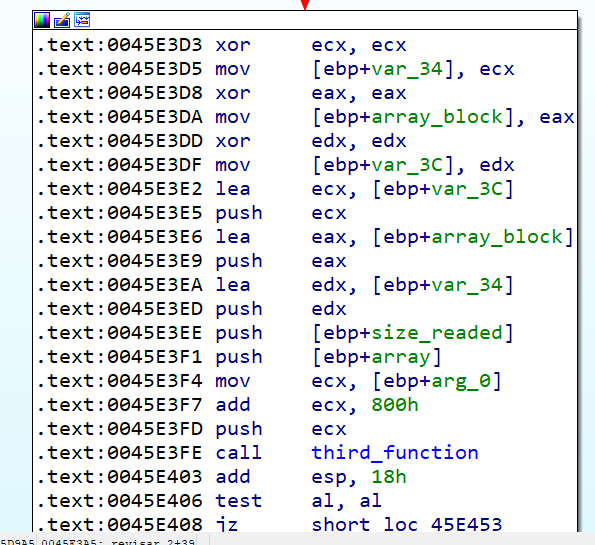

This array will be later used in the following function.

If we deep dive in this function, we could see it performs other operations over the buffer, but it can be bypassed in order to not need to implement more key generators in our python code.

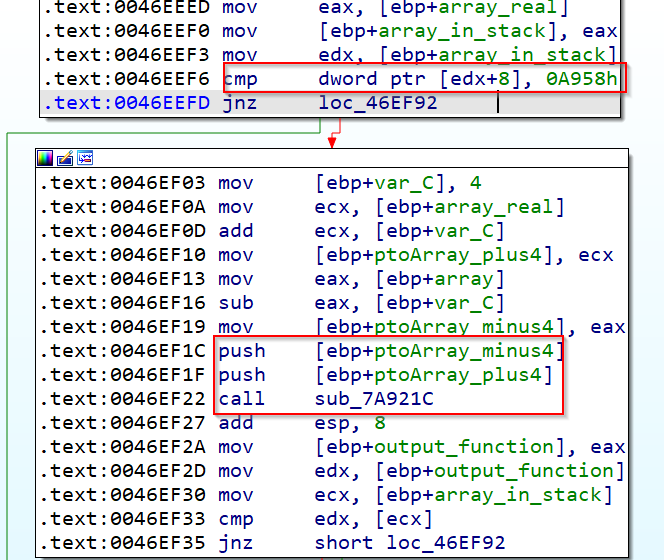

We see that third_function will firstly check if the array_buf+8 is equal to 0x0A958, and in case this check is passed, a new function will be called, with two arguments pointing to buffer-4 and buffer+4

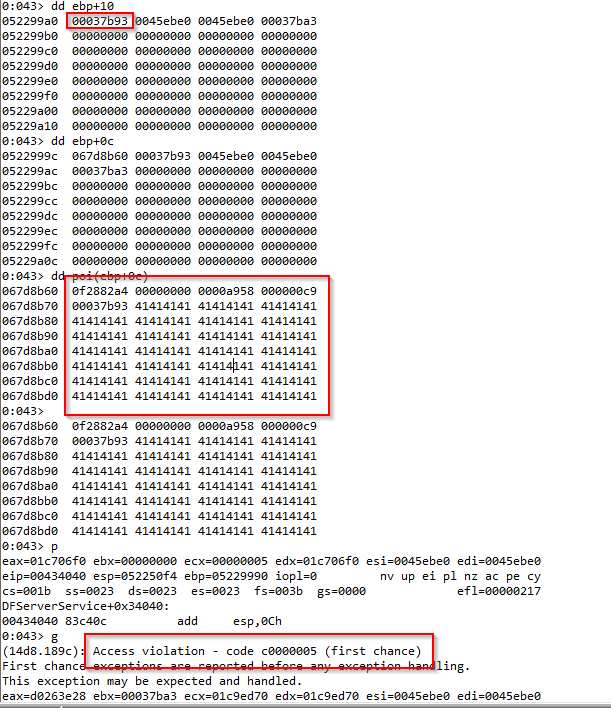

This function will always return a value depending on the input buffer, that we control, so we can get the output of the function with windbg, and copy it to our python script, in our case we are passing as argument to that function a 0x0, that will simplify the operations. We get the output of this function with WinDBG and update the packet we are sending to the server.

Our packet now looks like this

+-------------------------+

| First recv |

+------------------------ +

| 0xa37b0300 |

+-------------------------+

| Second recv |

+-------------------------+

| AAAA |

| offset to first memcpy |

| 0x0A953 |

| Size to new - offset |

| 0x0f2882a4 |

| 0x0 |

| 0x0a958 |

| Big chunk of As |

+-------------------------+

Now we have passed all the checks done to the received buffer, and we can analyze where our code will go next.

After returning from third_function, we see that if the return value is not zero, a new function will be called, in this case is a C++ method, so we will use WinDBG to see where it points really.

Doint that we see that call points to 00456EC8. Goind inside that function we see that again our buffer is passed as an argument to a new C++ method, that in this case, after being followed with WinDBG we see that points to 0042F970

And again inside this function we see another call that has our buffer as an argument, and yes, this will be the last one not really.

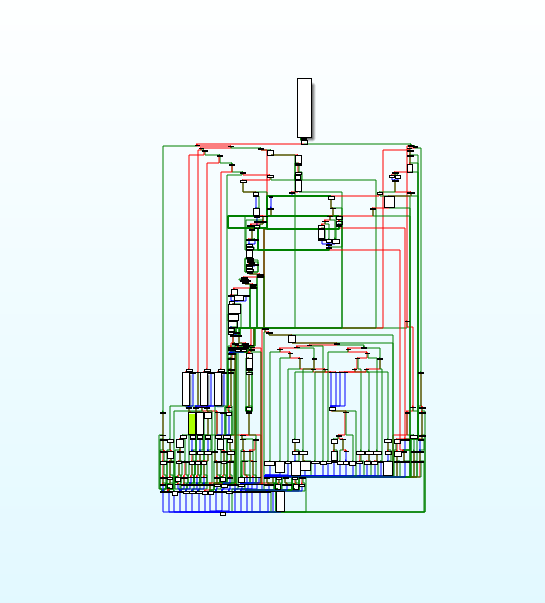

That call points to 0x42FA18, and inside that function we see a very big graph.

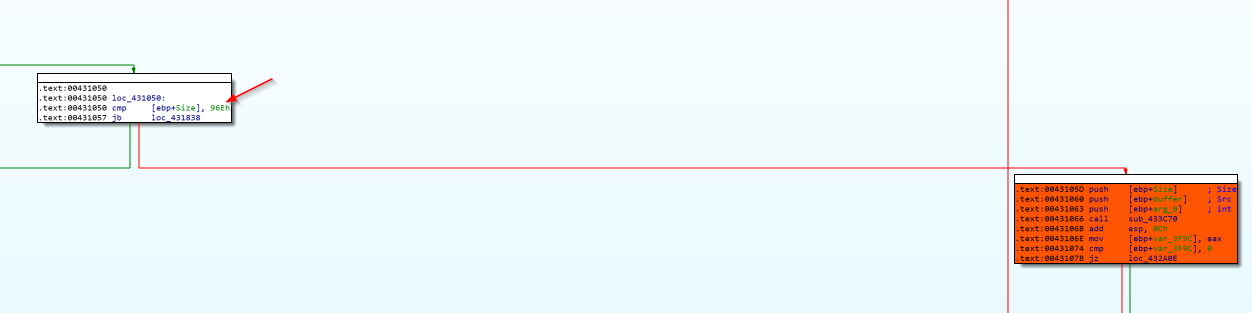

There we see a cmp ecx, 0CDh ;jg instruction, in this case ecx will come from arg_10 this is also under our control, it will come from the data below the last part of the buffer we are sending to the server, so after the 0x0A958 should go the 0x0C9 value (below 0x0CD), if we follow the possibilities after passing that check, we see that in 0x00431050 the size of the buffer we are sending is compared with 0x96E and if data is not below that value, the jump will not be taken, and we will go to another function (sorry, not was the last one).

This size value is not taken directly from a function that checks the size of our packet, instead, this size value is taken from a DWORD that we can send with our buffer. Finally our packet would be the following (and yes, this is the last)

+-------------------------+

| First recv |

+------------------------ +

| 0xa37b0300 |

+-------------------------+

| Second recv |

+-------------------------+

| AAAA |

| offset to first memcpy |

| 0x0A953 |

| Size to new - offset |

| 0x0f2882a4 |

| 0x0 |

| 0x0a958 |

| 0x0c9 |

| 0x00037ba3 - 0x10 |

| Big chunk of As |

+-------------------------+

If we follow the execution of this new function, we see that again size is compared against some values, and in case we send a size bigger than 0x0E74 we will trigger our vulnerability.

The vulnerability exists because the buffer pmallocado is initialized with a new function and size 0x0E74, and we are copying a buffer of 0x00037ba3-10.

Conclusion

After this long long long post we saw the process to reverse engineer a comercial software and discover vulnerabilitie. Other vulnerabilities exists, and some DoS vulnerabilities exist yet in the current version of the software.

Spaghetti Code is available in: https://github.com/waawaa/Exploiting-TIPS/blob/main/crash_faronics.py